Right now, companies are facing a severe crisis in leadership bench strength. Our Global Leadership Forecast 2025 revealed only 20% of companies have a strong bench. Why is this happening? One of the problems is that companies aren’t appropriately accelerating their high-potential talent for the challenges we face today.

And to be sure you have the talent you need at higher levels of leadership, you need to identify high potentials early, starting with your emerging leaders. In this blog, we’ll help you identify key challenges in identifying your high-potential emerging leaders, and how to start investing in them.

What Is High-Potential Talent?

First, let’s define high-potential talent. Simply, high-potential talent is someone who has the likelihood and ability to accelerate their growth to rapidly develop toward a future leadership role. The term can be used for people at any level, from individual contributors up to high-level executives. What’s important is that these are the people you are identifying to invest differentially for growth to fill your leadership pipeline.

Performance vs. Potential vs. Readiness

One of the key challenges is aligning the organization to understand the difference between performance, potential, and readiness. Performance is a measure of how someone is doing in their current role. Often, however, managers confuse performance and potential. They assume that a high performer automatically has growth potential and future ability to excel as a leader.

While sometimes that’s true, often high performers are experts at their current level. They don’t have the motivation, temperament, and/or skill to lead. Yet, many organizations invest in their top subject matter experts only to find that both the individual and their teams are dissatisfied in a leadership role.

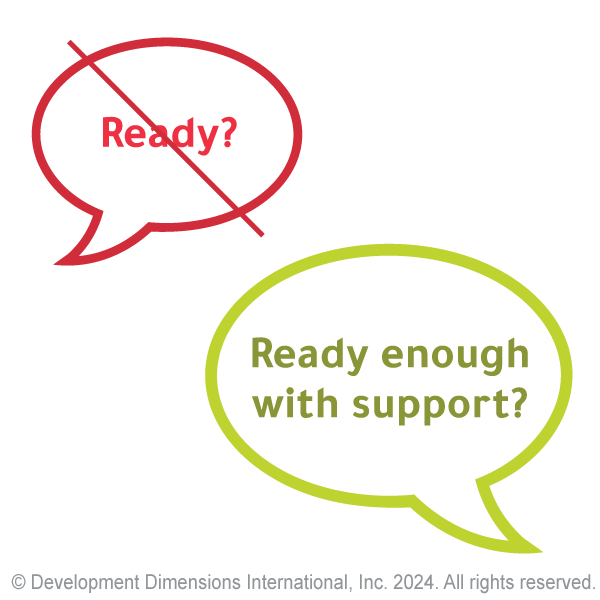

Readiness is more straightforward as it relates to how well someone fits a specific role or job type right now. That said, many organizations, and their leaders, struggle mightily with determining when someone is “ready.” A better question to ask is if the individual is “ready enough with support” to stretch into the next assignment.

Watch the video to learn how assessment helps you see beyond current performance to identify and develop leaders ready to take the next step.

Additionally, you need to ask how far out you are attempting to invest in your top talent. Some organizations will confuse readiness, the likelihood to perform well in the next level, with potential. Unfortunately, this mistake leads to investment in those who are likely “ready enough” and leaves out the “diamonds in the rough” who will see tremendous growth over longer periods of time.

Understanding these definitions and adopting a common language is one of the most critical steps in developing high-potential talent. If you don’t select the right people in your high-potential employee program today, you have almost no chance of having the leaders you need for the future.

Diversity in Your High-Potential Pool

Before we dive into the challenges of identifying and developing emerging leaders, it’s important to consider the role of diversity in developing high-potential talent.

One reason companies struggle to build diverse leadership teams is that their high-potential talent pools often lack a broad mix of perspectives. To ensure that the C-suite reflects varied ways of thinking and problem solving, companies must start by developing diverse talent at lower levels. When high potentials gain the right opportunities early on, they bring a wider range of experiences, fresh approaches, and sharper insights to senior roles over time.

But what do we mean by diversity? At its core, diversity is the range of identities and experiences that shape how people think, collaborate, and lead—both as individuals and as a team. Imagine how your culture could transform with a truly diverse group of people who challenge ideas, exchange perspectives, and work together in new ways. With a variety of mindsets, teams can tackle problems from multiple angles, engage in constructive debate, and make better decisions. These dynamics drive innovation, boost efficiency, and create a more resilient company.

The bottom line? Building a well-rounded leadership pipeline starts early. Investing in high-potential talent through growth experiences, mentoring, and career opportunities ensures your future leaders bring the diverse perspectives needed for long-term success.

7 Challenges in Identifying and Developing Emerging Leadership Potential

Here are seven challenges that can make identifying and developing emerging leadership potential difficult and how you can avoid them:

1. There’s a huge volume of people.

It can be overwhelming to look at the entire population of individual contributors to spot leadership potential. That’s why so many companies rely on managers to identify high-potential leaders (see next point). But you can put a number of systems in place, such as targeted, scalable assessments, that supplement manager ratings and help talent professionals look quickly and broadly across the organization to understand talent strengths and gaps.

2. Only managers can evaluate potential.

As mentioned above, many companies rely on managers to identify leadership potential. After all, managers see these employees in action. But most managers haven’t had any training on how to look for potential, avoid biases, and differentiate against performance and readiness. Without the right training and accountability, managers will fall back on the way they know best: looking at performance in the current role to determine potential for growth.

3. No clear definition of leadership potential.

Managers rarely have a clear, agreed-upon definition for leadership potential. So, they’re each left to come up with their own definition, which introduces inconsistency and inefficiency. This also makes your identification process ripe for bias as most managers will pick team members who remind them of themselves or of other current leaders.

4. Training isn’t focused on leadership.

Training and development for individual contributors is often focused on helping them get better within their current role. For example, they might be attending conferences in their field or getting additional certifications. While this isn’t a bad thing necessarily, it often comes at the expense of developing the leadership skills high potentials need to be successful in a future leadership position. We must democratize leadership development, and starting with high potentials is the next step.

5. Difficulty providing leadership exposure.

It’s great that you have identified leadership potential, but what are you doing to get these people ready for their next role? While development in the form of coursework provides valuable foundational knowledge, high potentials also benefit from direct exposure to leadership. On-the-job training and opportunities to “try on” leadership in a role simulation offer hands-on experiences to prepare high potentials for the challenges they may face in their next career step.

And usually, it’s even harder for organizations to get individual contributors leadership exposure, but bringing focus to this group is necessary. Don’t forget to include stretch assignments and other forms of leadership experience in the development plans for your early high potentials.

6. Managers aren’t trained to accelerate high potentials.

When organizations identify high-potential leaders, they typically rely on managers to spearhead their acceleration and development. But since few leaders are trained to do this, development quality varies across the organization. This approach also burdens managers with time-consuming responsibilities and diminishes the effectiveness of both the development programs and employee engagement. Not only that, but retention can suffer. High potentials are 2.7X more likely to leave in the next year if their manager doesn’t regularly provide opportunities for growth and development.

7. Leadership assessments are rarely used.

Given the high volume of people and informal approach, many companies don’t use assessments for leadership potential. But assessments are crucial. They help you to incorporate objectivity and find potential in talented people you otherwise might have missed. In addition, they can help give leaders specific direction about each potential leader’s strengths and challenges so they can guide their development with more intention.

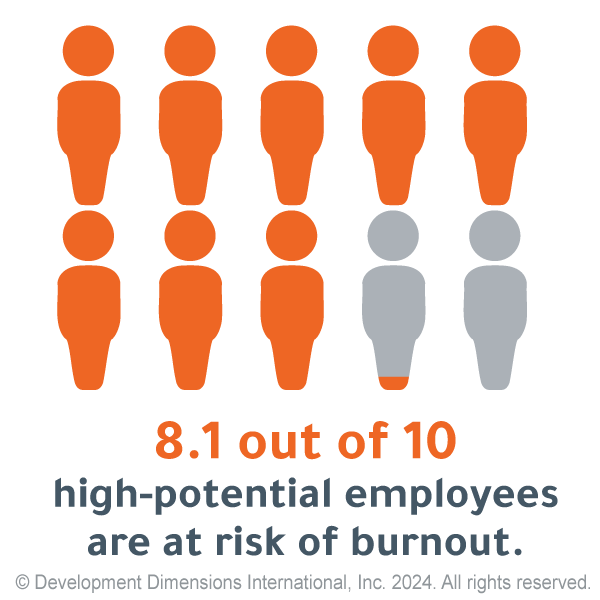

Watch for Burnout of High-Potential Employees

A word of warning: Once you’ve identified and start to develop your high-potential employees, beware of burning them out. These are the employees you want to retain most, but it’s easy to take advantage of them.

Because they tend to be high achievers and hard workers, it’s easy to ask them to take on more. And most likely, they’ll say yes.

We surveyed more than 1,000 high-potential employees, and 81% reported feeling used up at the end of their workday, much higher rates than any other population. And women, in particular, are also burning out at alarmingly higher rates.

But what’s even worse is that it’s common for high potentials to struggle in silence. Afraid of losing out on an opportunity, they may say nothing about their challenges. Instead, they may conclude that another job is the only way out. So you may not know that they are struggling until they leave. This highlights the need for a psychologically safe work environment—one where people feel empowered to speak up and share their challenges openly.

Invest in High Potentials Early

The future of your organization depends on your leadership. That’s why it’s important you have a bench of ready-now leaders and an effective high-potential employee program. To get there, you need to know who in your organization has the potential to lead. And then once you find them, invest in their development early.

Developing high-potential talent can’t be an afterthought and it can’t be left to chance. But with the right strategy and tools, you can identify leadership potential with clarity and fairness while gaining objective insights to target development. That way, your emerging leaders will have everything they need to succeed today—and tomorrow.

About the Authors

Kevin Tamanini is an I/O psychologist and Vice President of Professional Services at DDI. He oversees the post-sales teams responsible for designing and implementing innovative solutions for executive succession, leadership development, coaching, and development planning. He also has nearly 20 years of experience working with large-scale global customers across industries to implement talent development and selection programs for all levels of leaders.

Adam Taylor is a reformed child psychologist who found his place in industrial-organizational psychology and DDI. Based out of the Seattle area, Adam heads DDI’s Enterprise Client Success Practice and thrives supporting the implementation of multifaceted leadership programs for DDI's global partners.

Have a Question?

FAQ

-

What is high-potential (HiPo) talent?

High-potential (HiPo) talent refers to employees who demonstrate the ability, aspiration, and engagement to take on greater leadership roles in the future. At DDI, we help organizations identify and develop HiPo talent to build strong leadership pipelines.

-

Why is it important to develop high-potential talent?

Developing high-potential talent ensures organizations have a ready pool of future leaders who can step into critical roles. At DDI, we believe HiPo development drives business continuity, growth, and competitive advantage.

-

What are best practices for developing high-potential talent?

Best practices include providing accelerated leadership development, offering stretch assignments, building strong coaching relationships, and aligning development efforts with business strategies. DDI’s high-potential development programs focus on personalized, strategic growth experiences.

-

How does DDI help organizations develop high-potential leaders?

DDI offers high-potential leadership development programs that combine leadership assessments, targeted coaching, immersive learning experiences, and strategic succession planning support to accelerate the readiness of future leaders.

Topics covered in this blog